⚖

Knowledge E.T.C.

How to organize knowledge?

The attempt of modern science to create disciplines has lead to a wealth of specific, domain-driven knowledge. Great advances have been reached through the pursuit of the specifics. Technology, as a driver for applied science, has enabled entirely new ways for humans to inhabit our world. Nutrition, care, movement, outreach, communication, "E.T.C", are all domains of life that have been subject to radical transformations. First, the changes came through acknowledgment as objects for study and research. Second, they came from data gathering. And finally, the transformations happened by applying insights to the subjects themselves. The scientific methodology has inspired the rise of the specialist, reigning with authority over their domain.

However, we have been hitting a wall. The number of pieces gathered are greater than ever. We found ourselves stuck with the bottomless question of connecting them. Somehow, we humans have managed to have advanced in all directions at once without acknowleding the "big picture". The ubiquitous use of natural resources is deeply transforming existing ecosytems, leading to threatening phenomenons such as ocean acidification, depletion of ice at the poles and the rising temperature globally and locally. The disappearance of species which we share a great deal of similarities begs to question: how can we expect to survive in a poisonous environment?

So far, humans have extensively relied on our brain, our formidable organ, to face critical situations. Our brain is our capacity to apprehend and organize sensations and information. It informs our decisions and direct experience. Our network of problems is now a extricated at all scales, and domain-specific knowledge - while urgently needed - appears as only a fraction of the possible answers. For centuries, cities have embodied human networks, becoming the cradle of complex relationships. As we are close to reaching planetary urbanisation [^1], the multiple energetic, biological and informational layers of life reveals themselves, for they were always entrenched in the foundations of our social realities. Faced with all these pieces, we found oursleves quite inept at considering composing with them. Has our beloved human brain reached its limits? Or, did we fail at training it in a proper way? Somehow, ancient knowledge is lurking in the back somewhere, telling us we forgot how to be hollistic.

Socrates: I cannot help feeling, Phaedrus, that writing is unfortunately like painting; for the creations of the painter have the attitude of life, and yet if you ask them a question they preserve a solemn silence. And the same may be said of speeches. You would imagine that they had intelligence, but if you want to know anything and put a question to one of them, the speaker always gives one unvarying answer. And when they have been once written down they are tumbled about anywhere among those who may or may not understand them, and know not to whom they should reply, to whom not: and, if they are maltreated or abused, they have no parent to protect them; and they cannot protect or defend themselves

-- excerpt from Plato's Phaedrus

So what are we left with?

How can we make sense of what exists? Can the tools of the past solve the issues of the future? Arguably the most transformative and powerful tool ever created during the human reign is writing. Language was there first, then we managed to turn it into objects. Mapping, accounting, law making, or even poetry exists as attempts and strategies to make sense of the world. According to British anthropologist Jack Goody, writing is a "technology of the intellect"[^2] that allowed the spatialisation of thought. Lists for instance introduced a powerful tool for the organization of the mind, allowing new forms of deductive thinking. Not only do we keep records and archives, but we use these tools to support and structure our very human thoughts and organisations. With the evolution of writing comes the transformation of the mind - and the political organisation of societies.

Digital technologies are the continuation of this long history of writing. The 1nm (nanometer) photo-lithography process to imprint transistors onto silicon wafers to make micro-chips is a direct heritage of engraving. Beyond technical aspects, today's industries of writing also reproduce the power structures of the past, with power concentrated in the hand of a few of the beholders of secret texts, ruled by an elective literacy and its very strong hermeneutics. Writing regulates territories, from mental representations to the office of the lawmakers. Memes and rules setup the distribution networks for imaginaries, and prescribe powerful models of representations to be used.

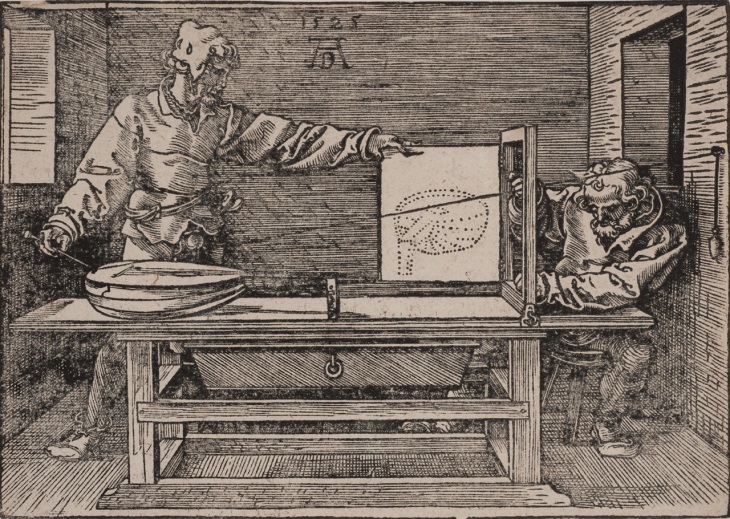

Durer, Albrecht (1471-1528) - Perspective Machine, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perspective_machine.

Since ancient times, mathematical writing systems provided rhythm for the arts and the world. Numbers and equations were the basis for all kinds of divination. The perspective for instance introduced a new point of view and transformed the way to conceive the world during the renaissance in Europe. It all started with painters building weird devices to look at the world (see fig below), and ended up defining some of the once largest and most powerful cities on Earth. Computers appear as the lastest iteration to date, where writing machines based on binary logic run the most sophisticated organizations in the world.

So how should we write today?

To write has become so cheap and ubiquitous that we forget the central importance of this activity. I found myself repeatedly considering "writing" as not even worth the time spent. Then, I think of my day spent coding, emailing, chatting, or even paying with my bank card. Its is yet another day spent writing. But, as soon as I want to write something meaningful, I found myself depleted of necessary human resources thinking "writing doesnt pay a dime". Perhaps my mind is stuck within rigid formats where I end up thinking, "Can I send you that bit of code with my article?" Any aspiring academic or journalist knows that feeling. Some years ago, I met with a well-aged anthropologist that explained to me how he was making a living as a student by writing encyclopedia articles. I thought it was very cool. What happened? Why can't I give form to valuable knowledge and get rewarded for it? Then it struck me. What I was doing by writing code was similar, only 30 years apart.

So much knowledge is stuck, out there. Scientific publishing is in the middle of a horrible war where academics are troops and ideas are casualties. Art publishing is flying high in elite spheres without any end-destination in sight. Web publishing is lost somewhere, busy with contemplating its fantastic new muscles in the mirror. Each people group in these domains are seeking their own unified approach to writing in order to exert control and claim territories. All of them contain gems to be reused in the vast world which somehow can help make sense of what is happening.

Here, we should not seek a general writing system, but a diverse set of possibilities, tools and authoring styles. Like other languages, the grammar of digital technology only exists in the making. Important explorations are still to be conducted in multiple domains of our representation-making-activities to invent new mental models, develop new tools, and create new ways of observing. Objects deemed inadequate may be excavated in order to give birth to their own activity.

This is the emerging roadmap for SCALE, to support numerous ways for humans and writings to evolve. SCALE is a digital-first publishing outlet, to experiment with the energy spent by machines to write. SCALE is a place to reflect on and figure out some new technics, based on spatial and digital forms. The format is fluctuating, because we are learning as we go. It involves incredible spatial transition from transistors to planets - and back to people and machines, in the form of code, text, and digital/physical objects. SCALE faces the paradox of writing today: we need to write more, but writing is killing us. Each new line of text printed, each new data processing task launched, each new transactions on a chain converts living matter into solid blocks. The only way is forward. We keep experimenting because we secretely hope we may continue to write without hurting ourselves.

Bio

Clément Renaud investigates how technologies can be used to create new forms of writings, spaces and representations. He is the Executive Direcotor of Qiware which publishes Scale.

[^1] Neil Brenner and Christian Schmid, “Planetary urbanization,” in Matthew Gandy ed., Urban Constellations. Berlin: Jovis, 2012 [^2] Goody, -- missing ref --